STEMMA

Systems of Transmitting Early Modern Manuscript Verse, 1475-1700

College of Arts, Social Sciences & Celtic Studies School of English and Creative Arts

We were very fortunate to have three undergraduate interns join our team in Galway this summer. We are excited to share a guest post by Cate Milley, an English major at Lehigh University. – Erin

When you think of Early Modern writing, you probably picture a white man sitting alone in a room, with a single candle lighting his work. However, the reality of Early Modern writing was much more diverse, and these manuscripts reflect the diversity of the individuals and culture that created them. Furthermore, people from various other identities were able to write and publish their own pieces. Different religions and ethnicities have representation in works from this period. However, one identity, I have found, has a very limited selection to choose from: the disabled. While not necessarily the disabled themselves expressing themselves in manuscript form, the lack of disability at all in these works is striking.

Disability in Early Modern Europe is a rather complicated matter. One might assume that Early Modern institutions and individuals had strong, negative opinions about the disabled, and that they acted in that manner. While that was certainly evident, as seen in the Poor Laws which punished those seen as impotent and poor, the Early Modern period birthed a changing attitude in which disability was not feared. For example, Phillippe Pinel’s “Moral Treatment” was one of the first approaches to healthcare that moved away from abusive treatments for mental illness and shifted to more humane therapies (Parallels In Time Part One: A History of Developmental Disabilities).

Despite the enormous progress individuals of this era made, there was still the underlying issue of “why.” Why are these wealthy institutions attempting to help the disabled? The answer may be because of a selfish duty they felt. Many rich benefactors were known to give funding to hospitals and buildings not because they felt sympathy, but in order to secure their place with God. Therefore, the progress made was not initiated from a place of purity and care, but one of self interest.

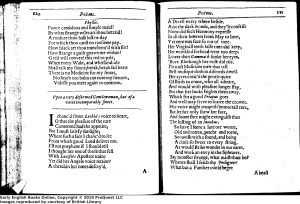

Returning to manuscript culture, I found only a few poems that discuss disability. As disability care and advocacy became more prominent, one might think that works about the disabled would also increase. I, however, found this to not be true. The poem I will focus on is titled “Upon a very deformed Gentlewoman, but of a voice incomparably sweet,” written by Thomas Randolph in 1630. It tells of a narrator who finds a woman with a voice like “Lesbia,” which references the ancient poet Gaius Valerius Catullus’s lover, signifying a sweet and lovely quality to her voice. However, once the speaker gets a look at her face, they are horrified at how hideous she appears, dramatically different from her voice. The speaker uses phrases such as “Yet nere was face so out of tune” and “Her wrinkled forhead went too deep” to express their disappointment and frustration at the disconnect between her voice and facial features. They also state that they believe the Gentlewoman “fell,” insinuating her place in Hell with “Lucifer.”

On the surface, this poem is an attack on a lady the speaker encountered, nothing more. However, the word “deformed” in the title suggests that this poem could take on a deeper meaning. This descriptor was commonly used to describe those with disabilities, as seen in everything from The Hunchback of Notre-Dame by Victor Hugo to the film Elephant Man. Therefore, I would argue that the Gentlewoman the speaker is referring to has a form of disability, which leads to the speaker’s disgust. Beyond disgust, the speaker feels a sense of deception, having first heard her sweet voice and then seeing her frightening face. They were expecting a woman of equally beautiful face and voice, which turned out to be incredibly inaccurate and led the speaker to take out their frustrations on the “deceptive” woman.

This depiction of the Gentlewoman, and the speaker’s intense reaction, is extremely problematic when viewing it through the lens of disability. By expressing their frustration with the deception they felt, it could be argued that this poem labels the disabled as manipulative and cunning, adding to stigma this population already endured. The speaker even goes so far as to compare the Gentlewoman to a “witch,” perhaps one of the more famous examples of deceiving women. The speaker’s severe dissatisfaction reinforces the idea that physical differences correlate to moral dishonesty, an opinion that was extremely prevalent at the time this poem was written. The Gentlewoman’s body, therefore, is viewed as a perpetrator of discomfort because of this problematic viewpoint.

The poem is not a short one; it repeats the speaker’s dissatisfaction over and over. One cannot overlook this detail, which emphasizes its importance. The persistent mockery and judgment towards the lady invites the reader, both of that time period and modern times, to join in on ridiculing the Gentlewoman. Whether Randolph wrote this poem with this intention in mind, disability is seen as a laughing matter, which brings up further questions regarding how bodily differences are viewed in literature and society.