STEMMA

Systems of Transmitting Early Modern Manuscript Verse, 1475-1700

College of Arts, Social Sciences & Celtic Studies School of English and Creative Arts

Skull and Crossbones as part of the Lynch memorial window on Market Street, at the back of St Nicholas’ church. The plaque reads: “This ancient memorial of the stern and unbending justice of the Chief Magistrate of this city James Lynch Fitzstephen elected mayor AD 1493 who conde[mned] and executed his own guilty son Walter on this spot has been restored to this its ancient site AD 1854 with the approval of the town commissioners by their chairman V. Rev. Peter Daly vicar of St. Nicholas.”

Nestled on a small cobbled street just off of Galway’s main thoroughfare, St Nicholas’ church is the largest medieval parish church still in use in Ireland, founded in the 13th century. Part of the wall of the churchyard on bears a rather bleak and unique memorial; known as the ‘Lynch house’, the wall includes stones from the house of James Lynch Fitz Stephen, a 15th century mayor of Galway, known for executing his own son, Walter. Along with a plaque, this memorial also features a large skull and cross bones carved into the churchyard wall. More skulls can be found inside the church itself: a medieval gravestone, brought in from the churchyard, bears a faded emblem, and a large granite obelisk in the centre of the graveyard, a memorial to three men – Thompson, Kinead, and Roberts – who drowned in the nearby river Corrib in 1887, is carved with the Irish harp, the symbol of the Claddagh, the Galway coat of arms, and, finally, a skull and bones framed with the phrase ‘Memento Mori’. Though hard to miss in a graveyard, these skulls were designed to remind the onlooker not only of death (fun), but also to live life well and with purpose (fun, this time without sarcasm). These graves or memorials are not just markers of death, then, but of a full life lived before then – except, perhaps, for Walter.

Faded skull and crossbones on a headstone discovered in St Nicholas’ churchyard

‘Memento Mori’ skull and crossbones on an obelisk for Thompson, Kinead, and Roberts, St Nicholas’ churchyard

This memento mori – Latin for ‘remember that you will die’ and a common feature of medieval art and literature – is also the focus of British Library Add. MS. 18044. An octavo miscellany of 180 leaves, MS. 18044 is filled with poems and epitaphs on the theme of death – cheery stuff! The manuscript is written in one single hand, likely Marmaduke Rawdon, whose name appears on the title page, ‘Collections out of seuerall Authors by Marmaduke Raudon Eboracensis 1662’.

Among the poems are five drawings: a diagram on the Holy Trinity; a clock face; and three small skulls, each attached to a different entry in the miscellany. Rather than marginalia, these illustrations are right in the middle of the page, often integrated as part of an entry’s heading. This begs the question – in a miscellany full of poems about death, why are there only three skulls? What makes these entries so special? And perhaps most importantly of all – how many rabbit holes can I go down trying to figure this out?

MS 18044 f.77r | MS 18044 f.80v | MS 18044 f.146v

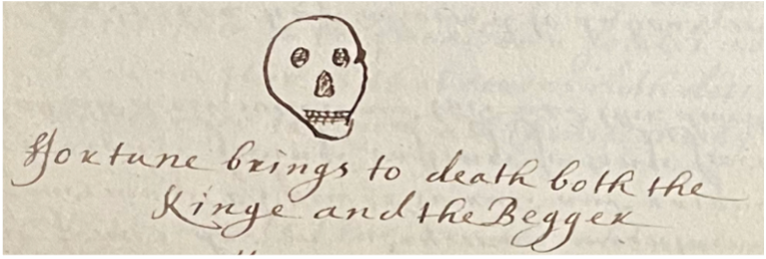

MS. 18044 f.146v

The first of these skulls (or, at least, the first we’ll look at here) comes with the shortest of the three entries: “Fortune brings to death both the Kinge and the Begger”. Though this could be the opening line or title of the poem that follows on for the next two folios (making it very much not the shortest of the three skull entries), the two texts have very little in common. Though it wouldn’t be the first time that had a poem has nothing to do with its title, this still seems unlikely. The manuscript’s own index (f.181r -188v) simply catalogues this under ‘death’ which, aside from stating the obvious, does little to help identify where the line comes from – or indeed, why it gets a skull.

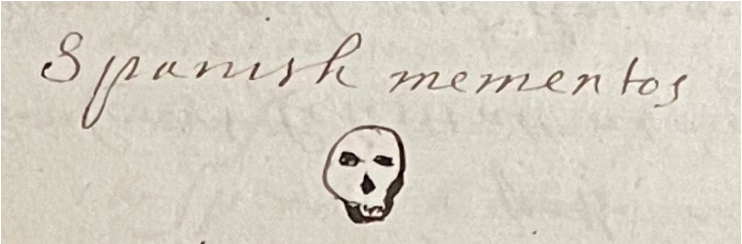

MS. 18044 f.80v

The second skulls is a little more intriguing, and comes attached to one of only two Spanish poems in the miscellany. It’s also the only one of our three skulls where we can find an author (though the poem has no attribution in the miscellany itself): our deathly doodle appears beside a version of Friar Pedro de los Reyes’ ‘Yo para que nací’ or ‘What was I born for?’ – close to, but sadly not, Billie Eilish’s song for Barbie. MS. 18044 has some differences or elements missing from the extant modern version of the poem, as seen in the comparison – Rawdon’s version skips line 1, introduces a new line in place of lines 5 and 6, and misses or misspells some words, suggesting either an imperfect copying, or that Rawdon found a variant to transcribe.

Yo para que nací

Yo para qué nací? Para salvarme.

Que tengo de morir es infalible.

Dejar de ver a Dios y condenarme,

Triste cosa será, pero posible.

¿Posible? ¿Y río, y duermo, y quiero holgarme?

¿Posible? ¿Y tengo amor a lo visible?

¿Qué hago?, ¿en qué me ocupo?, ¿en qué me encanto?

Loco debo de ser, pues no soy santo.1

Spanish Mementos

Que tengo de morir es Infalible

dexar de ver a dios y condenar me

triste cosa es pero posible

—

Posible y rio y Juego y canto

que hago en que mi ocupo y encanto

loco deuo de ser pues no soy santo

But this is not the most interesting thing that finding the poem’s origin gives us. Rather, de los Reyes was only born in 1557 – just five years before the date of compilation written at the front of the miscellany. Though we cannot discount that de los Reyes was a – deeply morbid and existentially obsessed – child prodigy, it’s probably more likely that the miscellany was not compiled in one single stint in 1662, and was put together over a much longer period. Though this itself is still a cool finding, we haven’t quite answered the question – why the skull?

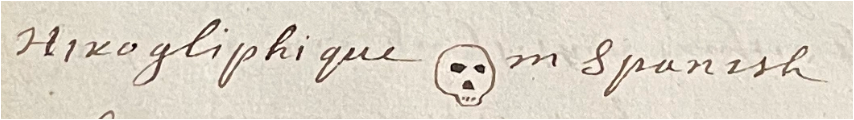

MS 18044 f.77r

Our last skull might give us the best guess at why these skulls were added, and comes attached – surprise! – to the only other Spanish poem in the miscellany. Titled ‘Hirogliphique in Spanish’ (spoiler: no hieroglyphs included), the poem opens with the couplet ‘como me ves te veras / como te ves yo me vi’ (‘As you see me, you will see yourself / As you see yourself, I saw myself’), a common Spanish saying often explicitly used as a memento mori. Variations of this phrase appear repeatedly across cemeteries and gravestones in the Spanish speaking world, including on the grave of an infamous pirate and the wall of the Wamba ossuary, the largest ossuary in Spain containing the bones of over 3,000 people.2 The poems are not entirely the same, however: whilst the inscription in Wamba continues “Todo acaba en esto aquí. Piénsalo y no pecarás”, Rawdon’s continues differently, and for much longer: “y pues tu as de ser asi / viva bien y viveras / viva bien entre la gente / y viveras siempre en paz / y con tu dios viveras /en el cielo eternamente.”3 The differences show that Rawdon didn’t get his copy from Wamba, but it might be a clue to where the poem did come from – and the reason for all the skulls.

This clue might be seen in a similar – but skull-less – poem elsewhere in the miscellany, an English poem that sounds remarkably like ‘Como me ves te veras’:

As I was soe be yee

as I am you shall be

what I gaue that I haue

what I spent that I had

thus I counte all my cost

what I left that I lost.

(MS 18044, f.85v)

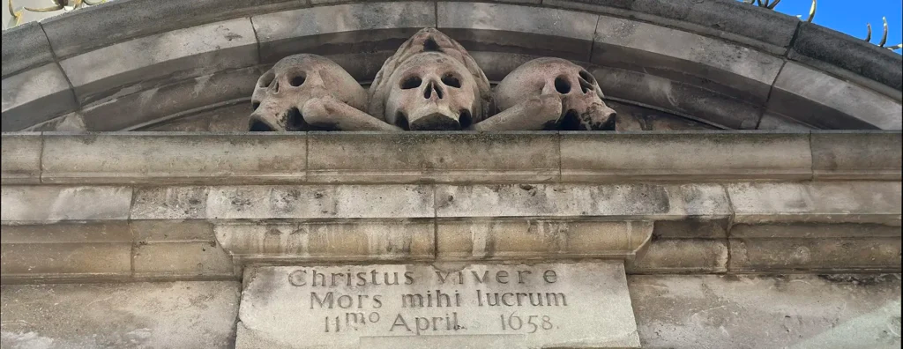

Perhaps most significantly, the poem is headed ‘In st Olaues Hart Streete’ in the miscellany , a well-known cemetery in the centre of London where, amongst others, Samuel Pepys is buried. Just like St Nicholas’ in Galway (see, there was a reason for all the skulls at the beginning!), St Olave’s is best known for the giant skull and crossbones on the cemetery gate erected in 1658, described by none other than Charles Dickens as “larger than life, wrought in stone.”4

Churchyard Gate in St Olave Hart Street Church, London, erected 1658

https://saintolave.com/index.php/our-story/

According to the STEMMA database, ‘As I was so be yee’ appears in two other miscellanies (Ashmole 38, Bodleian Eng. Poet. e.40) ascribed specifically to St Olave’s church, but it also appears titled as an epitaph ‘On Scaliger’ (Folger V.a.339), ‘On John Orgen and Helen his wife’ (Osborn Collection, Yale University, fb.143), and, most commonly, ‘On William Lambe’ (Folger V.a.180, BL Add. 27406, Pierpont Morgen Library MA 1057, Osborn Collection c.81/1). Another similar poem (‘As you are now So was she’) also appears in Sloane 2623. This conceit was obviously a popular motif in both English and Spanish poetry then, with this particular English version appearing in multiple places as epitaphs for different people. But why does the Spanish version get a skull in Rawdon’s manuscript and the English doesn’t?

If you’re looking for guesses (and I hope you are!) then my hunch is this: what if Rawdon was taking inspiration from where he found these entries? What if, just like Galway and London, the skulls were carved on to gravestones, and had poems with them? Rawdon travelled to many countries, including Spain, so it’s not implausible that he saw these poems at local cemeteries – this might also explain the variation to or personalisation of both ‘Como me ves te veras’ and ‘Yo para que nací’. In contrast, he might have easily picked up ‘As I was so be yee’ from other miscellanies or circulating manuscripts in England, without actually needing to visit St. Olave’s itself. Appearing later in the miscellany than its Spanish counterpart, Rawdon might have even copied ‘As I was so be yee’ because of its similarity to his already-copied ‘Como me ves te veras’. The visitation of one grave but not another would at least explain the appearance of a skull with only one version of the poem; more broadly, these grave visits might explain why, in a miscellany of poems about death, only three have skulls drawn with them.

This is my best guess, but without scouring an untold number of cemeteries and graves in England and abroad, this will just remain a hunch. Markers of real life epitaphs or just doodles to break up the drama? We may never know – after all, dead men tell no tales…