STEMMA

Systems of Transmitting Early Modern Manuscript Verse, 1475-1700

College of Arts, Social Sciences & Celtic Studies School of English and Creative Arts

“Investigating misascribed works might only rarely lead us to add a literary piece to an author’s canon. But such research can quite frequently lead us to insights about early modern England, its writers, its readers, and their reception of particular authors – not bad for dubious company.” – Lara Crowley, “Attribution and Anonymity,” 147.

Growing up in the late 90s and early 2000s, movie rentals were a big deal in my family. We lived a twenty-minute drive outside the city, and it wouldn’t be all that uncommon for us kids to go an entire week without making it into town. My mom, on the other hand, worked in the city and would regularly swing by the video rental store to pick something up for a movie night. Tired after a twelve-hour shift with a drive still ahead of her, mom would really just want to get in and get out (and who could blame her?). Unfortunately, this made her the ideal target for the strange phenomenon of the cinematic mockbuster.

ILC’s Hercules: The Invincible Hero (1997) and Disney’s Hercules (1997)

Throughout the 90s and early 2000s there was a thriving industry of budget films, especially children’s films (you can still find some even today), that piggy-backed on the marketing and publicity of major titles like those that Disney and Pixar released. If you have a favourite film from this era, chances are there is a B-movie version of it. Films based on IP outside of copyright—Pinocchio, Aladdin, Beauty and the Beast, The Little Mermaid—were especially susceptible to these strategies because other companies could use the exact same title, but a quick search will turn up everything from children’s movies like Tappy Toes, What’s Up? (for Pixar’s Up), and Chop Kick Panda to great action titles including Atlantic Rim, Independents’ Day, The Fast and the Fierce, and Paranormal Entity.

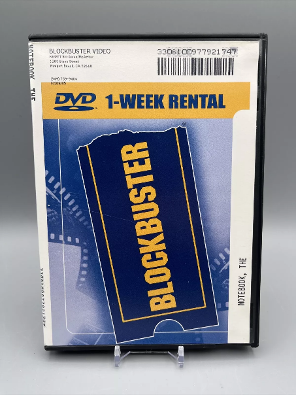

Maybe you think this is a ridiculous way to develop and market films? Younger readers especially might be wondering how anyone could fall for this kind of thing: there’s a clear difference in budget/quality even at first glance of the cover art. But this trend makes sense once you know what a 2000s rental case looks like.

Blockbuster levelled the advertising field by placing all their rentals in identical cases (possibly so that they could more effortlessly rent those cheaper films as well), and someone could easily make the mistake of grabbing the wrong film off the shelf even if they knew what they were looking for.

So it was that every once in a while, my mom, without the energy to perform a full investigation at the rental store, ended up bringing home a dud of a film when we all thought we were about to see the latest and greatest thing in home entertainment. I would politely watch the film alongside my siblings for as long as it could keep our attention, but deep down I couldn’t help but feel we’d been cheated out of the real deal.

*

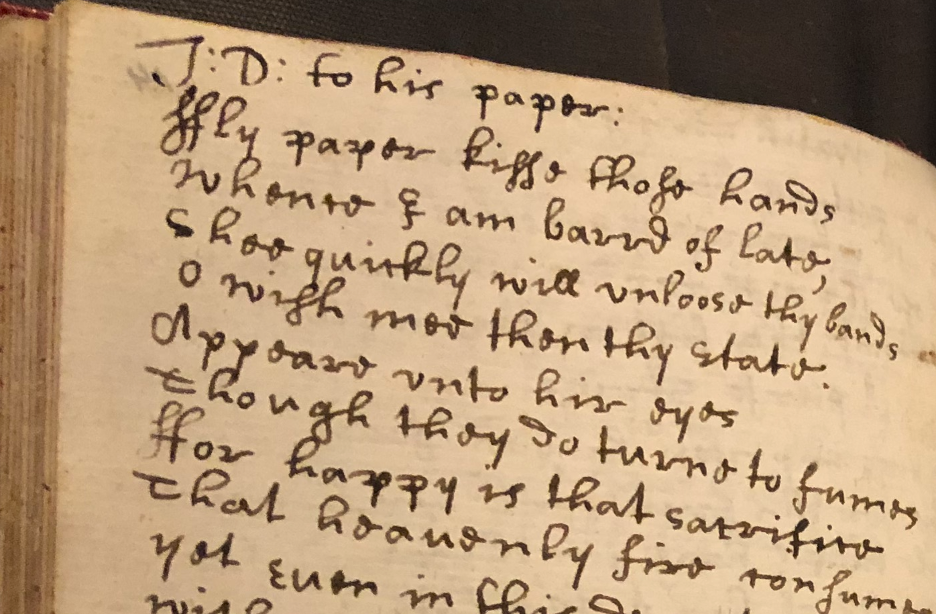

What, you might be asking, does all of this have to do with early modern manuscripts? Just the other day, I was working my way through British Library Add. MS 30982 as part of my work on the STEMMA project. I’ve been particularly interested lately in the verse and prose that early catalogues like CELM overlook (I find a certain kind of mischievous glee in the juxtaposition of a memorial poem for the Duke of Buckingham placed just a few folios apart from verse memorializing a “Senior Academick Mouse” – a story for another time!), and while I was comparing my images of the manuscript to the Folger Union First Line Index of English Verse, I happened upon this poem on folio 13v:

This is the moment where my mind flashed back to those mockbusters of my youth and that strange feeling of being cheated out of the genuine article. Only, instead of poorly animated characters or low-budget action sequences, this is a rather simple poem of rhyming couplets marketed with Donne’s initials and emulating one of his best verse letters.

At first glance, it is entirely plausible that someone could have mistaken this poem as Donne’s. “Fly paper kisse those hands” has a clear counterpart in Donne’s “Mad Paper stay,” a verse letter to Magdalen Herbert. Each poem opens with an apostrophe (direct address) to the letter, and both make mention of that letter being burnt up. The imitative poem’s command that the letter “kisse those hands / Whence I am barrd of late” is another connection with Donne’s letters: though it is a common enough trope in the early modern period (William Strode’s poem on f. 24v employs it, for instance), Donne uses some version of the phrase “with this letter I kiss these hands” in nearly twenty prose letters of the period.

Donne has a number of Dubia misattributed to him, of course, but this is different. This is not merely a poem scholars or scribes have potentially misattributed to Donne (one has to be careful about presuming too much about the scribe’s “J. D.”), this is a poem that imitates Donne in conceit, phrasing, and style, circulating alongside Donne’s own poetry and that of his contemporaries, While it may not be the genuine article, we ought to contemplate the implications of such poems even in terms of manuscript culture and reader reception.

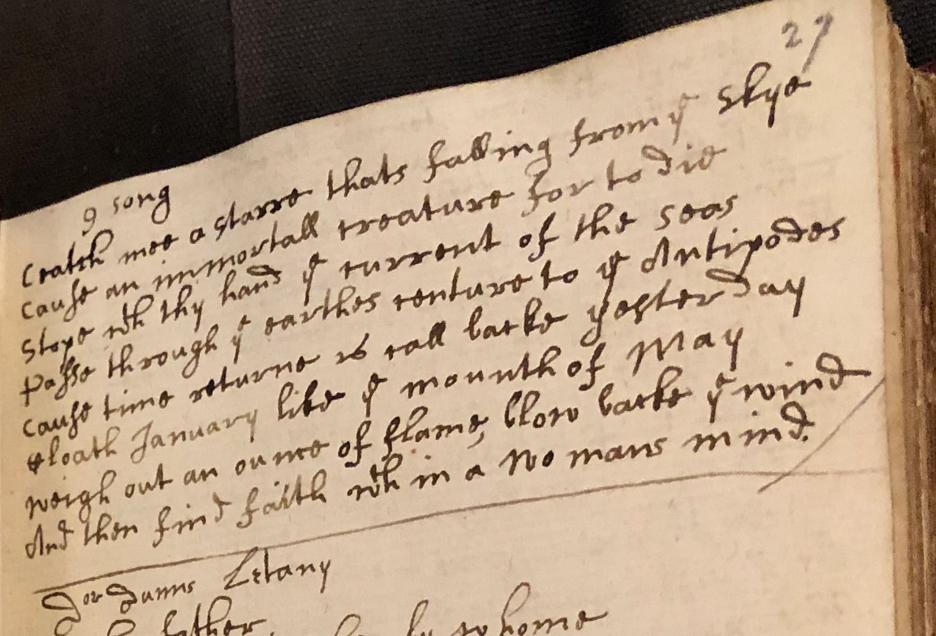

Take, for instance, this eight-line poem labelled “Song 9” (there is no Song 8) in the same manuscript (BL Add. MS 30982):

The poem reads:

Catch mee a starre that’s falling from the skye

Cause an immortall creature for to die

Staye with thy hand the current of the seas

Passe through the earthes centire to the Antipodes

Cause time returne and call backe yesterday

Cloath January like the mounth of May

Weigh out an ounce of flame, blow backe the wind

And then find faith within a womans mind.

Anyone familiar with Donne’s poetry will find a striking resemblance between this misogynistic little poem and John Donne’s “Goe, and catche a falling starre.” In fact, one would be hardpressed not to read the above work as a sort of simplified ripoff of Donne’s poem, a poetic mockbuster. The first poem’s opening line is clearly a rough rewording of Donne’s own, and the conceit of both poems—to list a number of impossible things alongside the notion of a faithful woman and therefore equate them—is identical. The imitating poet even rounds out their poem with a rhyme found in “Goe, catche a falling starre”: “blow backe the wind / And then find the faith wihin a womans mind” (7-8) clearly imitates Donne’s “And finde / What winde / Serves to’advance an honest minde” (7-9).

And there are even more generic echoes of Donne’s work in “Catch me a starre.” The poet asks the reader to “Cause time returne and call back yesterday,” an oddly similar line to Donne’s own “Tell me, where all past yeares are” (3); even the copying author’s allusion to the Antipodes (and all the strange wonders associated with that term) aligns well with Donne’s imagery of singing mermaids, “strange sights,” and “Rid[ing] ten thousand days and nights” on a journey to find a “woman, true and fair.”

But despite all their similarities, “Catch me a starre” falls flat largely because it delivers its message with a straight face where its counterpart operates on a level of instability that calls the speaker’s integrity into question. Donne’s poem begins in a similar fashion to “Catch me a starre”: the speaker asks the reader to venture out and find the answers to impossible questions, to perform impossible tasks, and, when the reader returns, the speaker insists that the reader will report that nowhere among these adventures was there “a woman true and fayre” (18).

Yet the certainty in Donne’s poem collapses: the speaker immediately capitulates their first assertion, allowing for the possibility that the reader could, in fact, find such a woman. He writes, “Yf thou findst One, lett mee knowe / Such a Pilgrimage weare sweete,” (18-19), but he immediately changes his mind once again, exclaiming “Yet doe not, I wold not goe,” because “Shee / Will bee / False, ere I come, to two, or three” (25-27). How strange that, in the midst of describing the inconstancy of women (this is even the title given to Donne’s poem in some manuscripts), Donne’s speaker has proven himself laughably inconstant, changing his mind three times in the space of just a few lines. When paired with the stilted triple rhyme that ends each of the poem’s three stanzas (“Or finde / what winde / serues to advance an honest minde”; “And sweare / no where / Liues a woman true and fayre”; “Yet she / will be / false ere I come, to two or three”), the speaker’s own inconstancy calls his character into question and frames him as an unreliable narrator (perhaps even a jilted lover?).

However misogynistic Donne’s poem might be to our modern sensibilities, those frequent turns that the poem hinges upon creates a sliver of doubt that destabilizes the speaker’s position and questions how seriously we ought to take his words. Written without that turn, “Catch me a starre” falls flat. The poem lacks personality, and a dour condemnation of all women replaces the playful tone of its predecessor.

The strange part is that there is little to no distinction between “Catch me a starre” and other, better (or at least better known) poems in the manuscript. The scribe numbers it as “Song 9” above the poem just as he numbers a dozen other poems, from William Strode’s “To Sir John Ferrers for a Token”, to poem’s as obscure as the other “Song 9” in the manuscript, “From the Temple to the Board” (f. 35v).

Even worse for fans of Donne, “Catch me a starre” is reasonably popular, with fourteen extant witnesses in manuscript according to the Folger Union First Line Index. For comparison, Donne’s “Goe, catche a falling starre” appears in just over forty manuscripts. However, only half a dozen of those witnesses explicitly mentions Donne as the author in some way. Perhaps even more interesting, while compilers may have been aware of the difference in these poems, they often left no evidence that this was the case. Both of these poems usually circulate anonymously and they, along with a handful of other poems, sometimes even carry identical or nearly identical titles related to women’s inconstancy. This raises an important question: did readers of “Catch me a star” ever read that poem thinking that it was Donne’s “Goe, catche a falling starre”?

There is no concrete evidence, at least, that this is the case. In no extant witness that I can find does a compiler ever attribute “Catch me a star” to John Donne. Moreover, the poems only appear together in two witnesses. In Beinecke Library Osborn b.200, “Goe, catche a falling starre” receives no attribution, only the title “Woman’s Inconstancy” (p. 92), and “Catch me a star” is similarly titled as “A Womans Fayth” (p. 3). However, in British Library Stowe MS 962 the compiler of the manuscript is discerning enough that the scribe subscribes Donne’s poem with the initials “J. D.” for this poem and many others by Donne in the manuscript, indicating to the reader that these are written by the same author. He even records Donne’s name in full alongside his Paradoxes and Problems at the beginning of the manuscript (an attribution that, if we are to believe Donne himself and his contemporaries, may have mortified him). “Catch me a star” receives no such attribution here, only another brief title, and it is not close in its arrangement to the clusters of dozens of Donne poems that appear in the manuscript like “Goe, catche a falling starre” is.

So how exactly was “Catch me a star” perceived in circulation? One can imagine a case where a reader happens upon this poem and mistakes it for Donne’s. For instance, “Catch me a star” appears directly before Donne’s “A Litany” in BL Add MS 30982. That compiler titled the latter poem “Doctor Dunnes Letanie,” and it is certainly possible a reader might want to associate these two poems with one another based on position.

Alternatively, we might read “Catch me a star” as a reading of Donne’s poem. The author of this imitation reads no nuance or complication in Donne’s work (or doesn’t care), only an invective against the character of women. Could this be a woman’s reading, someone fed up with the supposedly clever verse of the Donne the Wit, and so she reduces it to what she hopes is its least compelling version?

Or perhaps this really is just a mundane imitation of Donne’s work written by a fan whose poetry circulated in Donne’s shadow, riding Donne’s coattails with a reasonable level of popularity given its relationship to an extremely popular poem in manuscript. Is it a competitive market, making “Catch me a star” a sort of bootlegged ripoff of Donne’s poem? TheTappy Toes to its Happy Feet? Could it be an uninspired imitation in a context of sociable exchange? Or maybe the poem is a consolation prize for compilers without access to the genuine article?

Whatever the “real” reading may be, we need to consider that the poetry of Donne and other major authors was circulating in a sea of texts that are relatively unattended by modern critics, and that those texts communicate with, respond to, and engage these authors and their works even as they may have challenged and muddled them for early modern readers.

As instructors, introducing students to these contexts has the potential to be a great pedagogical tool. For instance, we might normally invite them to read only a handful of the thousands of sonnets that survive; is there a teachable moment in offering up a really rotten one just to demonstrate how good some other poems are? Doesn’t reading Donne’s “Go, catche a fallinge starre” in light of “Catch me a star” enrich our appreciation of the former?

Addendum

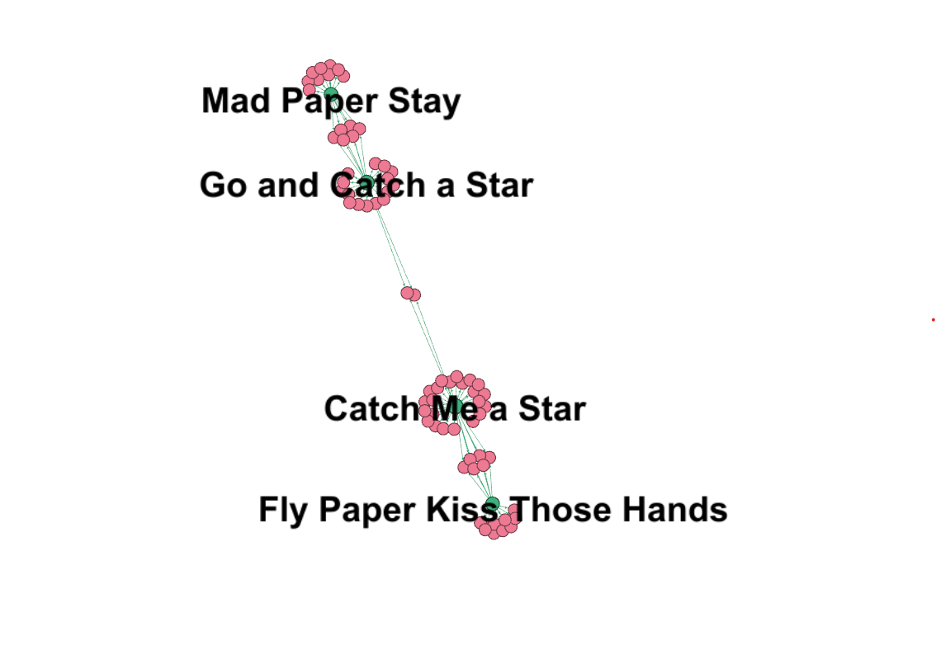

I was also very interested to discover that like circulates with like. This visualization of data I pulled and curated from an early version of the STEMMA database tells that story. Each pink node in the visualization above is a manuscript, and the edges between pink and green nodes indicates that the corresponding poem is present in that manuscript. While the star poems circulate together in two manuscripts, the paper poems never appear together. Perhaps more fascinating (but not surprising?), even this small data set reaffirms our notions of authoritative manuscripts, as Donne’s poems circulate with one another just as frequently as their imitations circulate together. I’ll be particularly curious to see if this remains true when exploring the STEMMA network at scale. Such experiments will give us another method of verifying how valid our perceptions about authoritative readings might be, and they will also help us see whether authoritative readings in a single manuscript persist across authors and poem types. In other words, is an authoritative manuscript of Donne’s poems more likely to contain authoritative copies of the work of other authors or other poems in general?